As death threats surge, First Amendment advocates struggle to say what's a crime and what's protected

As the first Black columnist at The Daytona Beach News-Journal, Michelle Ferrier wasn't shocked by hateful calls, emails and letters. She simply placed them in her "red folder."

But one persistent correspondent got her attention with vile manifestos full of slurs, predictions of a race war and a warning: "I'm coming for you."

"When you receive a threat like that, it's like a bomb dropping on your house," Ferrier recalled of the 2006 missive. "You don't know who to trust, who to turn to."

She went to the police, but they had neither the manpower nor the technical savvy to track down an anonymous perpetrator.

The letters got more menacing. Ferrier said she grew so fearful she self-censored her columns, hoping to tamp down the hate. She stopped going out in public. She guarded her kids.

Around the 10th letter, she told her boss she was quitting, moving the family and changing careers. Ferrier became a university professor and later executive director of the Media Innovation Collaboratory in Tallahassee, Florida.

She went on to found TrollBusters, training and assisting journalists victimized by online harassment. Ferrier said she remains conflicted about how far society should go to protect the free speech of threateners who squelch the First Amendment rights of others.

"It's a legal quagmire," she said. "But they do not have the freedom of speech to say, 'I'm going to kill you.'"

As national politics grow more volatile, death threats are surging against public figures and officials. But legal experts say prosecutions are rare because of the difficulty deciding what counts as a true threat and court rulings meant to protect free speech.

Amid that confusion, those who promote First Amendment rights – some of whom have been targets of terrorizing messages themselves – struggle to draw a line between free expression and criminal acts.

How should society differentiate between felonious words and protected speech?

How can a right that was codified by men firing muskets address modern threats made via social media, emails, or text messages?

Those questions have become a chorus amid increasing violence and vitriol triggered by enforcement of pandemic precautions, election disputes, racial unrest, police abuses and other hot-button issues.

The dilemma – free speech versus freedom from fear – is compounded by the United States Supreme Court’s failure to clarify which threats are punishable offenses and which are protected.

Lower courts, trying to carve out exceptions to the First Amendment, have added to the confusion. In some jurisdictions, a death threat is criminal if it would scare a reasonable person. In others, a threat is unlawful only if a perpetrator intended to terrify a target.

Combine that ambiguity with the struggle to identify perpetrators and you have a system in which police seldom arrest suspects, prosecutors rarely file charges and perpetrators keep making threats.

That leaves election officers, educators, journalists, public health officials, police officers and others fending for themselves.

The difference between hyperbole and danger

If the First Amendment is a double-edged sword, Johnny Williams has felt both blades.

In 2017, the sociology professor at Trinity College in Connecticut used Facebook and Twitter to share an article on racism. His posts included words from the article such as, “Saving the life of those that would kill you is the opposite of virtuous,” plus a hashtag that said, “Let. Them. F---ing Die.”

Williams, who believes race is a social construction, contends he was merely calling for the eradication of white supremacy. But, in response, conservative groups besieged him and the college with menacing calls and emails.

“They still come in every now and then,” Williams said. “It’s basically, they’re going to come and kill me and my family. … My wife was terrorized.”

Williams said some threats were traced to a man in California who had a terminal brain tumor; the suspect was not charged. Others were traced to a teenager in Ohio. “His parents were really upset,” Williams said. “He apologized, crying.”

Williams said he was unsurprised by the lack of prosecutions because he doesn’t expect the justice system to protect a Black man. “It definitely didn’t work for me,” he said. “The double standard is always there.”

Although his saga is distinct, death threats have grown more common.

In Michigan, vote counters were deluged with threats as former President Donald Trump and his supporters claimed the presidential election had been stolen. Only a handful was arrested and prosecuted.

One of them pleaded guilty but mentally ill after threatening Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and Attorney General Dana Nessel. He got five years of probation.

Henry Reichman, a professor emeritus of history at California State University, East Bay, said legal murkiness is magnified by the fact that you discover whether a death threat is serious only if it gets carried out – and then it’s too late.

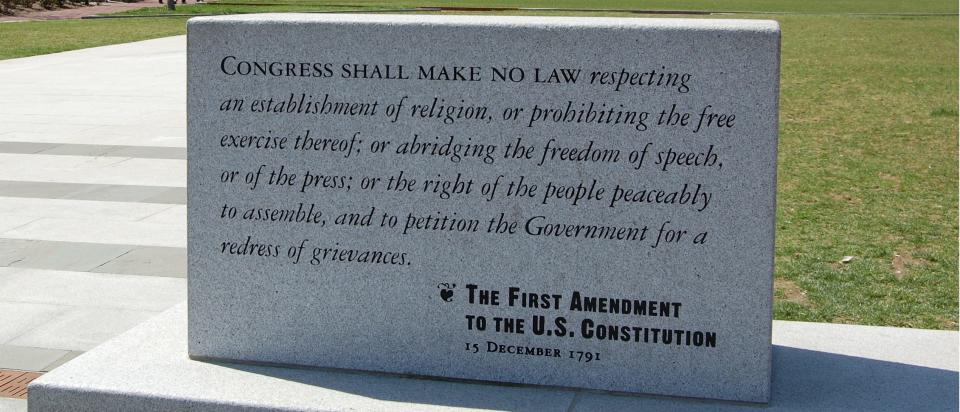

On the other hand, free speech was enshrined in the very first amendment to the Constitution because it is the founding principle for a democratic republic.

“It’s a very hard boundary to draw between exaggerations or stupid, dangerous statements and a real threat,” Reichman said.

Vietnam protester argued he wasn't threatening President Johnson

Treating death threats as crimes goes back to common law, which holds that placing an individual in fear of harm amounts to an assault.

But in American jurisprudence, when that principle collides with the First Amendment, the outcome is legal chaos.

The nation’s highest court has struggled to clarify what constitutes a criminal threat. As a result, noted the late Kenneth Karst, a constitutional law scholar, lower courts have come up with a hodgepodge of conflicting doctrines – “a set of abstractions offering minimal predictability of results from case to case.”

During a protest against the Vietnam War in 1966, 18-year-old Robert Watts announced that he had just been drafted for military service. “I am not going,” Watts said. “If they ever make me carry a rifle, the first man I want to get in my sights is LBJ."

Watts was convicted of a federal charge of making a threat against then-President Lyndon Johnson. On appeal, he argued that he had no intention of going into the military or assassinating the president, and his words were exaggerated, protected political speech.

The Supreme Court ultimately agreed. A majority of justices ruled that a criminal threat must be distinguished from hyperbole, but they did not define what constitutes a “true threat.”

In the aftermath, some lower courts established an objective standard, finding a threat unlawful if it would place a reasonable person in fear. Others devised a subjective standard, concluding that the perpetrator must intentionally or recklessly terrorize victims.

'This is not a threat'

Racial hate campaigns in Virginia gave the high court an opportunity to clarify in 2003. At issue was a statute that outlawed cross burnings. A majority of justices upheld the law, deciding that protections against terror can supersede First Amendment rights.

In 2015, many thought the Supreme Court was poised to resolve the confusion. A Pennsylvania man, Anthony Elonis, had been convicted on multiple counts for threatening his ex-wife, co-workers, a kindergarten class, police and an FBI agent via social media posts.

On Facebook, Elonis wrote after his divorce: “If I only knew then what I know now … I would have smothered your ass with a pillow. Dumped your body in the back seat. Dropped you off in Toad Creek and made it look like a rape and murder.”

Some posts were in rhyme or accompanied by another message: “This is not a threat.”

On appeal, Elonis contended he was an aspiring rapper whose declarations were a combination of artistic expression and personal therapy. He had no intent to kill, he asserted, and it didn’t matter that his ex-wife and others felt endangered.

Amid intense public interest, the Supreme Court heard arguments – and basically punted. The majority did not rule on key First Amendment issues. Instead, justices returned the case to a lower court, where Elonis’ guilty verdict was overturned and later reinstated.

Some experts concede that a smart perpetrator can evade conviction simply by laughing, putting a threat in verse, or using other pretexts for humor, art and satire.

Bradley Jackson, senior program officer with the Institute for Humane Studies at George Mason University, said he believes a threat should be criminal if it is made recklessly, whether the perpetrator intends to terrorize or not.

“Someone’s enjoyment of liberty in the absence of threats is one of the cornerstone purposes of a civil society,” Jackson said. “A threat is a threat. Reasonable people can tell the difference between a Nazi who wants you to fear for your life and a political person using a trope.”

Jackson said he'd like to see the Supreme Court take up another case. "These questions need to be answered.”

'Confused area of law'

James Weinstein, chair in constitutional law at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, said some may wonder if getting threatened reduces one's affection for the First Amendment.

In his mind, even staunch advocates recognize that true threats are no more protected than someone screaming “Fire!” in a crowded theater. "There are limits to free speech," he said.

Still, as Weinstein discussed Supreme Court rulings, he seemed to struggle. Setting fire to a cross at a Ku Klux Klan rally probably would count as protected political speech, he decided, but doing so on someone’s front lawn likely would be a criminal offense.

Asked how police, prosecutors, or citizens are to untangle such distinctions, Weinstein said, “It’s a very confused area of law.”

David Snyder, executive director of the nonprofit First Amendment Coalition, said the nation's founders wanted to protect people from government encroachment on free speech – not to insulate someone who makes specific threats of violence coupled with an ability to carry them out.

Snyder, a lawyer and former journalist, pointed to the Jan. 6 insurgency at the nation’s Capitol, where some in the crowd cried out, “Hang Mike Pence!”

If the words had been chanted at a rally in another state or even down the road, he said, they probably would have been construed as lawful, political rhetoric. But that day, the cry came from Trump supporters, some carrying ropes, as they assaulted police officers and entered the Senate chambers where Pence had been.

“That’s a real threat,” Snyder said, “a true threat.”

Increase in threats, but not prosecutions

Ed Leiter, a prosecutor in Maricopa County, described how Arizona’s criminal code handles threats.

If someone declares he is going to kill another person, Leiter said, that might be a misdemeanor under a law that prohibits “threatening and intimidation.”

If the message is sent electronically, it could qualify as a felony under a computer crime statute. And if the target is a government official and the purpose is to change public policy, a “terroristic threat” might be charged.

Asked how police and prosecutors decide whether a menacing statement is protected speech, Leiter said, “My answer is always: It depends. … There are tons of different variables.”

Leiter said Arizona has experienced a dramatic increase in the number of death threats against public servants in the past two years. Yet police have submitted only three cases for prosecution, and just two suspects have been charged.

Some police agencies have threat management units, he said. But perpetrators often can’t be traced, especially when they use social media. Those who are identified may be outside the country or mentally ill. And legal requirements for prosecution are difficult to meet.

Ashutosh Bhagwat, a law professor at the University of California, Davis, said he thinks jurisprudence on death threats is “absolutely clear,” though charges may be rare because prosecutors and police don’t believe they can get convictions.

However, he too wrestles with the legal nuances: If someone receives a message that says, “You deserve to have a bullet between your eyes,” that is not a criminal threat, he said. But if the message warns, “I have a gun and you deserve to have a bullet between your eyes,” that would be prosecutable. Or it might not, depending on context.

“Sometimes,” Bhagwat allowed, “lines aren’t very easy."

This article originally appeared on USA TODAY: Surge in death threats confounds First Amendment advocates