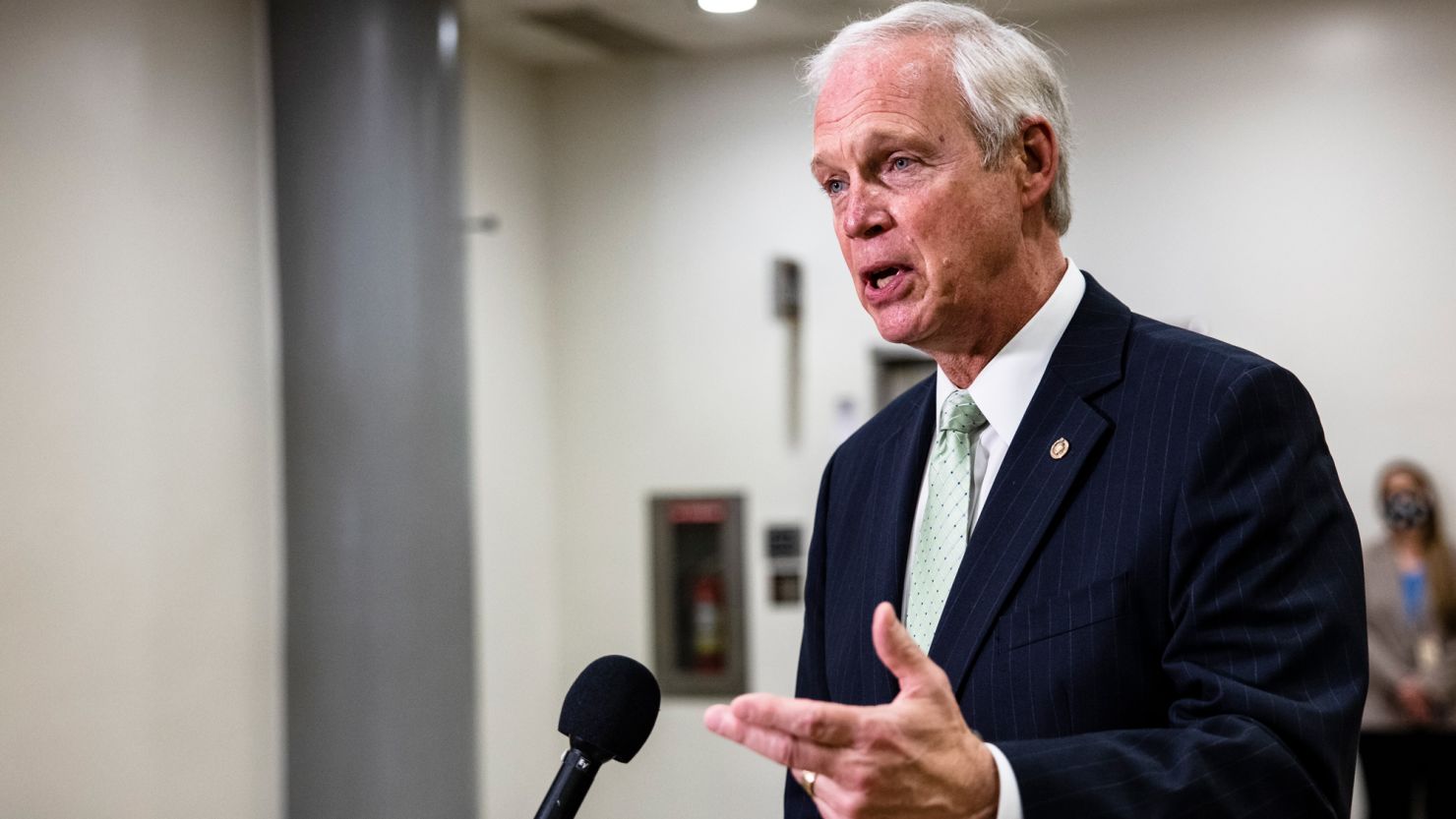

Wisconsin’s Republican Sen. Ron Johnson announced he was running for reelection on Sunday. That should be viewed as good news by Republicans, who need a net gain of just one seat in this year’s midterm elections to wrestle Senate control from the Democrats.

While we don’t know what the outcome of this year’s elections will be, history suggests that Johnson is likely to win and Republicans will not lose any of the seats they control to Democrats.

Why? Because the opposition party rarely loses Senate seats in midterms when those states had leaned toward them in previous presidential elections.

Let’s start with Wisconsin. President Joe Biden won it in 2020, but only by 0.6 percentage point. He won nationally by 4.5 points. In other words, the state voted nearly 4 points to the right of the nation.

The same was true there in 2016, when Wisconsin voted more Republican than the nation as a whole. Giving somewhat more weight to the most recent election (i.e. 75% to 2020 and 25% to 2016) reveals that Wisconsin is a little more than 3.5 points more Republican than the country on the presidential level.

Since 1982, opposition-party incumbent senators from states like Wisconsin (i.e. lean toward the opposition party in the previous two presidential elections) have won 86 out of 87 elections in midterms.

The fact that opposition-party incumbents like Johnson are so successful shouldn’t be surprising. There is usually some sort of backlash against the sitting president’s party in midterms. If an opposition-party member represents a state that is already less friendly to the president’s party than the nation, one would expect that an opposition-party senator would do well in a midterm.

Indeed, the only time an opposition-party senator lost (Republican Lauch Faircloth in 1998, to Democrat John Edwards) was when the backlash against the president’s party was muted. Faircloth’s loss came in a year in which the President, Democrat Bill Clinton, had an approval rating in the 60s.

Biden’s approval rating, right now, is mired at around 42% to 43% on average. It seems unlikely, at this point, that Biden will be popular enough for his party to overcome the traditional headwinds against the White House party this election cycle.

Broadening it out a little bit, every single Republican senator running in 2022 is from a state that has leaned more Republican than the nation as a whole in the last two presidential elections. That’s in large part because the 2016 election (i.e. when these senators were last elected) remains the only time in the last century when every state that had a Senate election voted for the same party in both the Senate and presidential races.

The chance that any of these Republican senators loses is small, if history is any guide. In fact, the correlation between the presidential lean of a state and how it votes in Senate elections has gotten stronger in recent years. In 2020, it was more than +0.9 (on a scale from -1 to +1).

(The growing correlation between how a party votes in Senate and presidential elections helps to explain why a number of Democratic incumbent senators lost in 2018. Although they were members of the opposition party with Republican Donald Trump as President, all the senators who lost were from states that leaned Republican on the presidential level.)

Democrats’ best chance to pick up a Republican-held seat is where Republicans are retiring. There are five of those seats, most notably in North Carolina, Ohio and Pennsylvania. All three voted more Republican than the nation in the last few presidential elections, but all have elected at least one Democrat to major statewide office in the last four years.

Still, even here, the math is not on the Democrats’ side. Since 1982, there have been 35 midterm Senate elections in states that leaned toward the opposition party in the previous presidential elections and where an elected incumbent was not an eligible candidate by the time of the election. The opposition party won 32 of the 35.

The three elections where the opposition party lost had one of two things going for it: Either the president had an approval rating in the 60s (2002 in Minnesota) or the president’s party had a popular governor running for the Senate seat (West Virginia’s Joe Manchin in 2010). In the case of 1998 and Indiana, Democrat Evan Bayh was a popular former governor and was running with a popular Democratic president.

This year, the President doesn’t look like he’ll be popular. Nor do the Democrats have someone running for any of these seats who has anything close to the history that Manchin has of winning in a deeply red state.

Of course, maybe there will be some surprising results this year. History doesn’t always hold. But if it does, the Democrats’ chances of picking up seats in the Senate are small.