Parents of teens and preteens say it used to be that they only had to worry about explaining the mechanics of sex and pregnancy to their kids.

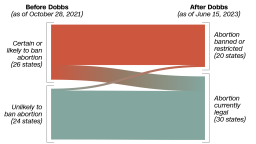

But since the US Supreme Court’s Dobbs decision ended 50 years of protected access to abortions in the United States last year, some families say these discussions now include details that sound straight out of a spy movie, including how to rent out-of-state post office boxes if they end up needing abortion pills, use WiFi in a public place and delete any personal details from phone apps that could track them.

These parents say the shifting legal landscape around reproductive health care has also brought new worries and a sense of urgency to conversations and decisions about birth control that might have been more distant considerations before.

Christine, a mother in southeastern Wisconsin, said she felt “shocked” and “sick” after the Dobbs decision became official. She also sprang into action.

CNN is not using Christine’s last name because she teaches at a Catholic school and feared that sharing her story could put her job in jeopardy. CNN isn’t using the names of her children to protect their privacy.

Two of Christine’s children are living at home: a teenage son and a daughter who is in her early 20s and moved in with her parents to save money while she finishes her degree.

Christine sees Wisconsin as a purple state that prides itself on its level-headedness. She says the horror of Dobbs was bad enough, but then a state law that had been on the books since the mid-1800s took effect, making it illegal to perform abortions except to save the life of a pregnant person. As a result, many providers have stopped offering terminations while legal challenges wind their way through the courts.

For Christine, as a parent, the biggest change since Dobbs is the feeling that she urgently needed to protect her kids. “Like I would do to help keep a child from backing off a cliff. That’s kind of where I feel it’s at,” she said.

She was a classroom teacher for 20 years, and “I’ve seen so many good kids make one bad choice that just changes their trajectory forever,” she said.

Christine realized she needed to urgently stress the risks to her son and one of his friends. The friend, she said, was “making bad choices.”

“I did lay into him,” she said, something she never would have done before the Supreme Court’s decision.

She sat both boys down and told them things were different now. The stakes for having sex were higher.

“I said, ‘you guys basically have to have a job if you want to have sex these days,’ ” she said.

She told the boys that if they were having sex, they also need some savings in case they needed to pay for their girlfriends to travel out of state to get an abortion.

“ ‘Kid, you better have two grand saved up, because guess what, Plan B doesn’t always work, right? And condoms don’t always work,’ ” she said. “ ‘Because you’re gonna have to go out of state, and you’re gonna have to go there stay for three days, so unless you’ve got that, I would best be making better choices.’ “

Christine said her son’s friend was in shock. “Nobody had ever talked to him about that,” she said.

For her 23-year-old daughter, the issues and the conversation were different. Her daughter has been on birth control since middle school for medical issues. In November, when she needed to renew her Nexplanon – an implant in her arm that releases hormones continuously for three years – the first provider she made an appointment with wouldn’t do it.

Right around that time, a conservative group called the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine and others sued to revoke the US Food and Drug Administration’s approval of mifepristone, a medication that’s used in abortion pills, creating a new front in the fight for access to reproductive health care.

After nurses asked Christine’s daughter a series of baffling questions about her age, her plans to have children and whether she had considered more natural methods of birth control, her daughter said, they refused to change her implant.

“They told me, ‘we’re going to have to hold off on this, or you may have to go find somewhere elsewhere, because this is not something that we are able to do as of right now.’ ”

Christine’s daughter isn’t sure why they refused. She said she was intimidated by the visit and afraid to probe further. Her best guess is that even though there are no legal restrictions on birth control in the US, this practice might have been anticipating some.

“I think that they were scared of the repercussions … of a potential legislation that could have been implemented within the next few months and be royally sued. Which is absolutely ridiculous,” her daughter said.

She was eventually able to find another provider who did the procedure, but the experience rattled her and her mom.

Christine said she and her daughter also made a plan for what she might have to do if she needed an abortion.

“We talked about how you need a burner phone” so it couldn’t be traced, Christine said. They talked about what states she could travel to if she needed a procedure and how to get abortion medications mailed if she needed them. “If that was the case, how could you get a P.O. box outside of Wisconsin to get it forwarded to you? We went through all of this,” Christine said.

They also discussed “on your phone, deleting any apps that track your cycle and how to handle medical bills,” Christine said.

Moving up the timeline

In Louisiana, where the Dobbs decision triggered a state law that banned abortion at any stage of gestation, except to save the life of the mother, Adam and his wife were discussing what they should do for their 15-year-old daughter, an honors student who competes on her school’s robotics team.

Adam shared his family’s story on the condition that CNN use only his first name to protect their privacy and safety.

“She’s a great student,” he said of his daughter. “She’s headed to college. She’s already made a 32 on the ACT, and she just finished her sophomore year in high school. So she’s got a bright future ahead of her, and we didn’t want this to be something that could derail that.”

They had planned to address birth control around age 16, he said, but after Dobbs, they worried that states might go after birth control access next.

“So we had talked about it with her before, and the decision to get birth control was really independent from the whole [end of] Roe v. Wade. Roe v. Wade thing just moved up the timeline,” Adam said.

When they tried to get an appointment to get her an intrauterine device, or IUD, which releases a low dose of hormones as a form of long-acting birth control, there was already a two-month wait, Adam says – suggesting that they weren’t the only ones who were thinking along the same lines.

Adam’s wife says that as they watched the news with their daughter after the Supreme Court ruling, they felt like they couldn’t wait.

“We just felt like our choices were taken away – as a female, over our body – and what’s gonna come next?” she said.

Their daughter says she feels more secure having the IUD, which should last until she is 22. They hope it will get her through at least an undergraduate degree.

“Whether she wants a new one put in or what, she’ll be in a different place,” Adam’s wife said, and can make the decision on her own.

These kinds of open and direct discussions about sexual health don’t happen in every family, of course.

For teens who can’t talk to their parents about birth control, a federal program called Title X, which provides family planning services at little or no cost to low-income patients and adolescents, has been a lifeline. But now that’s under threat, too.

Fighting for access

On the website of the nonprofit legal group Jane’s Due Process, a Texas-based organization that until recently helped teens access birth control without having to tell their parents, a banner pops up: “Safety Alert: Computer use can be monitored and is impossible to completely clear. If you need to exit this website in a hurry, hit the ESCAPE key twice.”

According to the reproductive health nonprofit Guttmacher Institute, 24 states require parents to give their permission before minors can access birth control, except under certain circumstances.

Texas is one of the most restrictive states in that regard. There, anyone under 18 needs their parent’s permission to get birth control – even if they’re already a parent themselves.

Until recently, there was an important loophole, however. Teens could get free, confidential contraception at Title X clinics in Texas and across the country.

In December, District Judge Matthew Kacsmaryk ruled that Title X was violating parental rights and state law by allowing minors to get birth control without their parent’s consent.

His ruling is being appealed. In the meantime, Title X clinics in Texas have stopped providing birth control to teens unless they get their parents’ OK. Advocates say it’s a devastating decision for the state, which ranks ninth in the nation for the rate of teen pregnancies, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Graci D’Amore, senior manager of direct services at Jane’s Due Process, said that after the Dobbs decision, Texas teens could still get birth control through Title X. Immediately, her group got an influx of calls and texts from teens looking for help getting to Title X clinics, which are concentrated in cities.

“Now, we’ve stopped advertising because there’s just no way for them to get it,” she said. Instead, she says, the group is raising money to help teens travel to other states for abortions.

“The more effective ways of preventing pregnancy are being completely taken away from teens,” she said. “Excuse my language, but it’s f**king atrocious and unjust, and teens, especially Texas teens, deserve better.”

One development that could ease access significantly for teens would be the availability of birth control pills over the counter. In May, experts who advise the FDA on its drug approvals voted unanimously that the FDA should green-light Opill, an over-the-counter option for hormonal birth control. The agency is expected to announce its decision later this summer.

If approved, the drugmaker says, Opill could be on pharmacy shelves by the end of the year.

Breaking the cycle

Kathleen was a teen mom and swore that she would never let her own kids follow that same path.

“I don’t want my kids to struggle financially like we did through the years,” she said. “I don’t want that. And I feel like I’m protecting multiple generations by choosing to discuss birth control options with my kids.”

She now has three girls and three boys. CNN is using only her first name to protect the family’s privacy.

Among her conservative friends and relatives in Florida, Kathleen drew fire with her decision to get birth control pills for her oldest daughter to help with a medical problem.

To them, she said, getting a teenager birth control was like giving her permission to have sex.

“My mother-in-law, she blamed me. She said, ‘Why would you put her on birth control if she’s not sexually active?’ ”

Her daughter started birth control pills for medical reasons but had significant side effects, and doctors said she needed a different option.

At a follow-up visit with the gynecologist, either her daughter or the doctor shot down one alternative after another. They ultimately left without getting anything.

Three months later, her daughter was pregnant at age 16. According to Kathleen, it happened one of the first times she had sex.

The family agonized for weeks about what to do. Kathleen said her daughter considered all her options but ultimately chose to keep the baby and is comfortable with that decision. The baby is due any day.

Last week, Kathleen asked another daughter who is 15 about what she wanted to do to protect her health and her future. The teen “hasn’t even had a kiss yet,” she says, but she knows how fast things can change.

“It’s more or less like, ‘this is how the world is right now,’ ” Kathleen says she told her. “ ‘This is what your sister has had to face and the situation that she’s in. This is what I’ve had to face being in that same situation, 17 years ago. How do you feel?’ ”

Kathleen says her 15-year-old is strongly against abortion. “She’s my more political child.”

“She did tell my 16-year-old that if she was to get an abortion, that she would never speak to her again,” she said.

Given her beliefs, she said, her middle daughter is choosing to get birth control, hoping she won’t ever have to face the decision herself.

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“She doesn’t want the pill because she doesn’t feel like she’ll be reliable taking it,” Kathleen said. “I think she’s more or less leaning towards the implant in the arm.”

Kathleen has also started talking to her youngest daughter, who is in the fifth grade, something she said she never would have considered before Dobbs.

“I’ve already started the conversation, just not as in-depth as I have with my 15-year-old, but more or less about her rights, her choices,” she said.

“I definitely feel like I’ve been pushed, not just because of the laws but the situation that we’re at home,” she said.

For now, she says, she’s working hard to support and protect her kids but knows that even her best efforts can only go so far. “No matter how much you try to teach them and guide them, they make their own decisions.”