On this day 2,067 years ago Julius Caesar was assassinated in broad daylight in the middle of Rome.

But it wasn't a mob or a popular uprising - Caesar was killed by a group of disgruntled senators.

Here's how it happened, moment by moment, on that fateful day in 44 BC...

But it wasn't a mob or a popular uprising - Caesar was killed by a group of disgruntled senators.

Here's how it happened, moment by moment, on that fateful day in 44 BC...

The year is 44 BC. Julius Caesar has just been declared "Dictator for Life" and is the most powerful man in the Roman Republic.

In 48 BC he had defeated Pompey the Great, another Roman general, and by 45 BC he had put down all other resistance - the civil wars were over.

In 48 BC he had defeated Pompey the Great, another Roman general, and by 45 BC he had put down all other resistance - the civil wars were over.

But a conspiracy was brewing against his life; the Senators were frightened by how much power Caesar already possessed and - crucially - by how much the people loved him.

They feared that, if he hadn't already, Caesar would turn the Republic into a kingdom ruled by one man.

They feared that, if he hadn't already, Caesar would turn the Republic into a kingdom ruled by one man.

So this was not an uprising of the people against a tyrant, but a small conspiracy of aristocrats and senators, about sixty of them.

Why did they decide to kill Caesar? There are two views. The first is that they wanted to save the Roman Republic from tyranny.

Why did they decide to kill Caesar? There are two views. The first is that they wanted to save the Roman Republic from tyranny.

Marcus Junius Brutus was the reluctant leader of this conspiracy. He was on Pompey's side during the civil war, but Caesar granted him amnesty.

Brutus was conflicted between betraying the man who saved his life and protecting the sacred and ancient Roman Republic.

Brutus was conflicted between betraying the man who saved his life and protecting the sacred and ancient Roman Republic.

A more cynical or realistic view is that these Senators saw their power threatened by Caesar, who didn't need their support and might, in time, circumvent them completely.

Rather than Brutus' lofty and noble ambitions, perhaps the conspiracy was simply a question of power.

Rather than Brutus' lofty and noble ambitions, perhaps the conspiracy was simply a question of power.

In any case, momentum reached fever pitch. Too many people knew about the conspiracy and time was of the essence before it got out.

They considered killing him at the elections in the Campus Martius, but then Caesar announced a special Senate meeting on the Ides of March...

They considered killing him at the elections in the Campus Martius, but then Caesar announced a special Senate meeting on the Ides of March...

In the Roman calendar there were three days in every month with special names.

The 1st was the Calends, the 5th (or 7th) was the Nones, and the 13th (or 15th) was the Ides.

It was based on the phases of the moon, hence why they varied from month to month.

The 1st was the Calends, the 5th (or 7th) was the Nones, and the 13th (or 15th) was the Ides.

It was based on the phases of the moon, hence why they varied from month to month.

The Greek historian Plutarch noted the irony that it was at the so-called Curia (Meeting House) of Pompey, built by Caesar's greatest rival, that this meeting of the Senate was scheduled to take place.

The Curia was just by the entrance of a large theatre also built by Pompey.

The Curia was just by the entrance of a large theatre also built by Pompey.

Nor was that the only twist of fate. When Rome had been ruled by kings in the 6th century it was another Brutus who led the coup against King Tarquinius Superbus and made Rome a Republic in the first place.

Five hundred years later his descendent would try to save it.

Five hundred years later his descendent would try to save it.

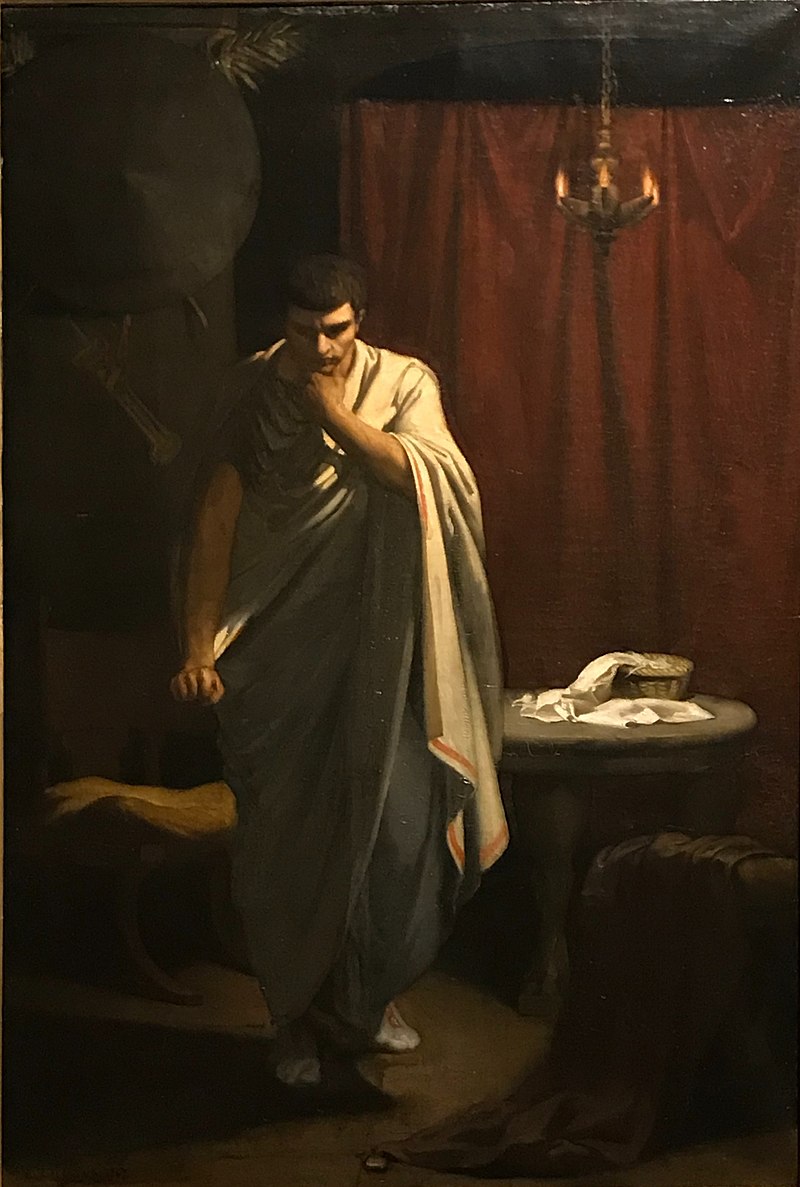

It's the morning of the 15th March.

Brutus, with a dagger under his robe, leaves his wife Porcia for the scheduled meeting - she fears something bad will happen and begs him not to go.

But he does. The conspirators are all gathered at the Curia of Pompey, waiting...

Brutus, with a dagger under his robe, leaves his wife Porcia for the scheduled meeting - she fears something bad will happen and begs him not to go.

But he does. The conspirators are all gathered at the Curia of Pompey, waiting...

Caesar is late.

He remains at home all morning because of bad health, strange dreams, and unusual omens over the last few days.

Caesar is spooked and, urged by his wife, decides to send Mark Antony to postpone the Senate meeting.

He remains at home all morning because of bad health, strange dreams, and unusual omens over the last few days.

Caesar is spooked and, urged by his wife, decides to send Mark Antony to postpone the Senate meeting.

But Decimus Albinus, one of Caesar's most trusted allies, is in on the plot.

He reminds Caesar that it was he who called the meeting, and suggests that the Senate are ready to proclaim him king if only he shows up - not to do so would be an insult to them and make him look weak.

He reminds Caesar that it was he who called the meeting, and suggests that the Senate are ready to proclaim him king if only he shows up - not to do so would be an insult to them and make him look weak.

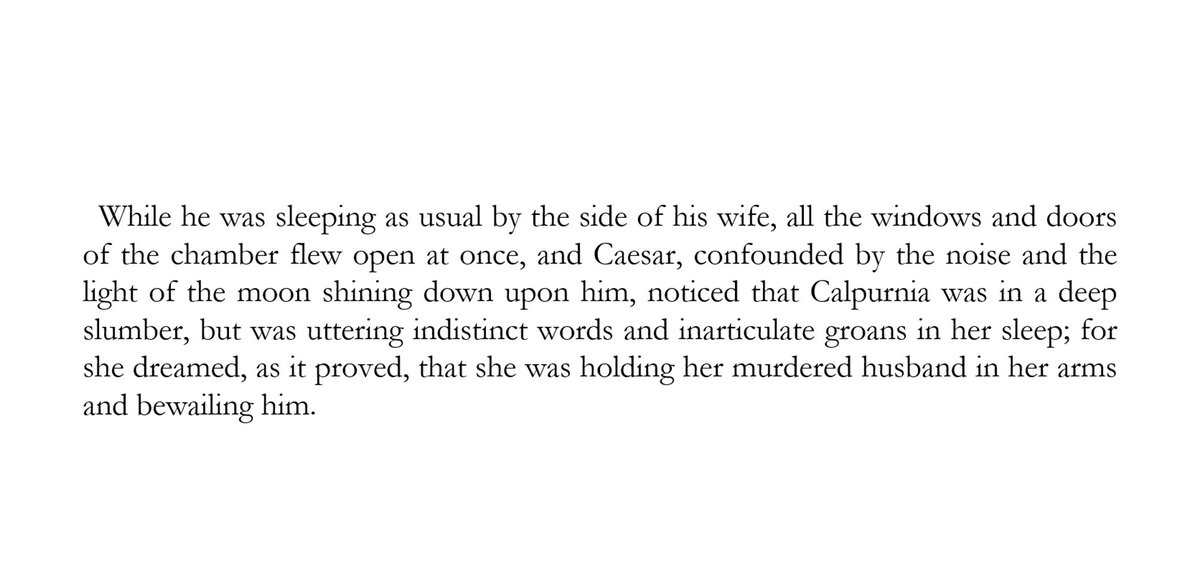

Still, Caesar is coming.

Allegedly a soothsayer called Spurinna once told Caesar to "beware the Ides of March." On his way to the Senate Caesar sees Spurinna and mocks his prophecy, saying, "the Ides have come."

Spurinna replies, "they have come, but not yet gone."

Allegedly a soothsayer called Spurinna once told Caesar to "beware the Ides of March." On his way to the Senate Caesar sees Spurinna and mocks his prophecy, saying, "the Ides have come."

Spurinna replies, "they have come, but not yet gone."

Meanwhile Brutus receives an urgent message to say his wife has died. She hadn't, as he later discovered, but he chooses to remain anyway.

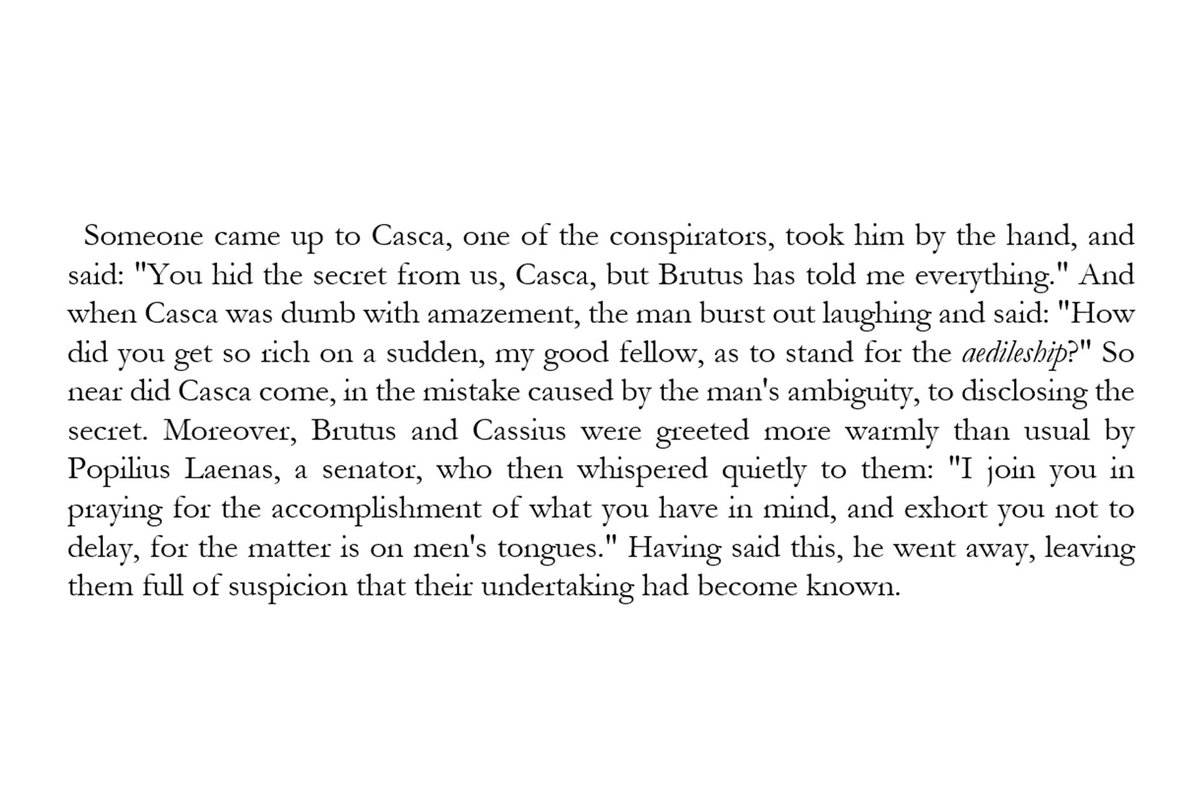

And finally Caesar arrives at the Curia of Pompey, but not without one final moment of panic, as the conspirators fear they are being outed.

And finally Caesar arrives at the Curia of Pompey, but not without one final moment of panic, as the conspirators fear they are being outed.

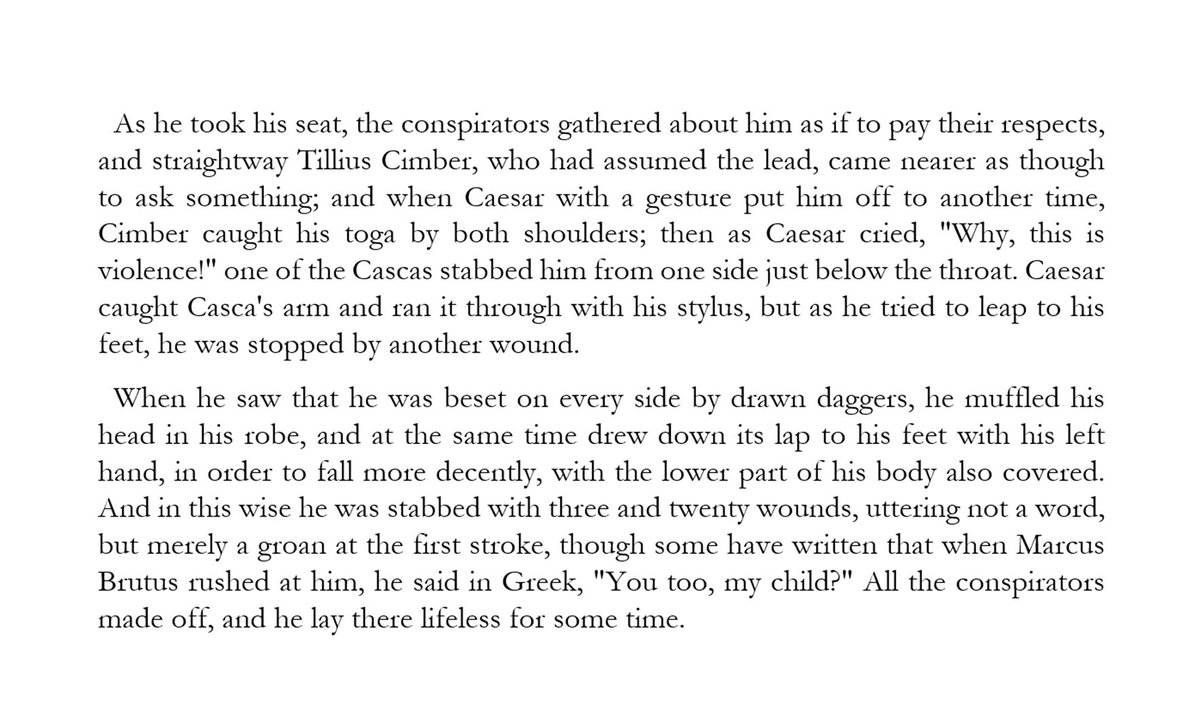

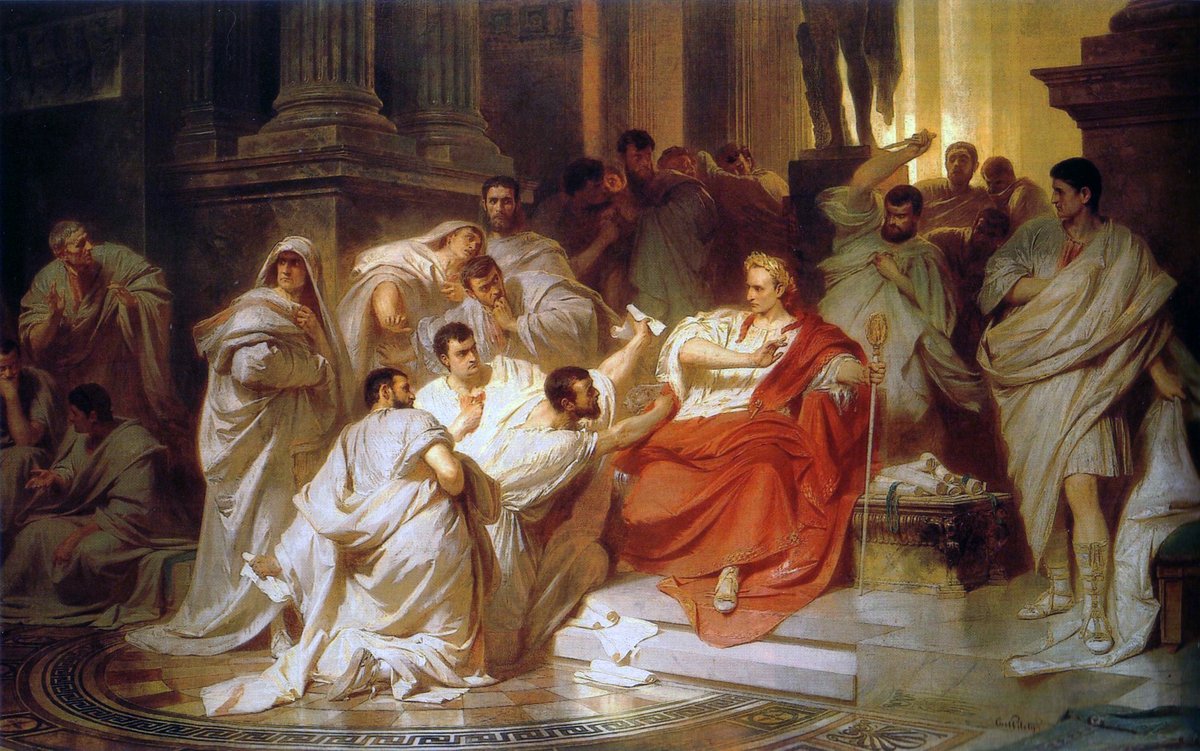

So Caesar enters the Curia.

Mark Antony, Caesar's close friend and ally, was a fierce soldier who might have been able to protect him. But Albinus delays Mark Antony outside; this was a crucial part of the plan.

Inside, Caesar is surrounded by the Senators...

Mark Antony, Caesar's close friend and ally, was a fierce soldier who might have been able to protect him. But Albinus delays Mark Antony outside; this was a crucial part of the plan.

Inside, Caesar is surrounded by the Senators...

The conspirators leave his body behind and the next part of their plan commences: to address the people, assuaging their fears and proclaiming liberty for all of Rome.

For that is how they styled themselves: as Liberators, not Conspirators.

For that is how they styled themselves: as Liberators, not Conspirators.

But Rome is eerily silent. The conspirators disperse and barricade themselves at home...

Next day Brutus addresses the people. It goes well until Caesar's will is read out by Mark Antony - he has left money to every citizen. A riot breaks out and they burn down the Curia...

Next day Brutus addresses the people. It goes well until Caesar's will is read out by Mark Antony - he has left money to every citizen. A riot breaks out and they burn down the Curia...

Mark Antony's plan works. The conspirators are frightened into believing the people are against them and scale back their plans for reform.

He urges peace, calms the people, and agrees a compromise whereby they are not punished, but all of Caesar's laws and reforms remain valid.

He urges peace, calms the people, and agrees a compromise whereby they are not punished, but all of Caesar's laws and reforms remain valid.

In the end another civil war broke out. The conspirators were defeated in 42 BC by Mark Antony and Octavian, Caesar's heir.

After that came *another* civil war between Antony and Octavian.

Octavian won and in 27 BC became Augustus, the first Emperor, and peace ensued at last.

After that came *another* civil war between Antony and Octavian.

Octavian won and in 27 BC became Augustus, the first Emperor, and peace ensued at last.

The reputation of Caesar's assassins has been mixed.

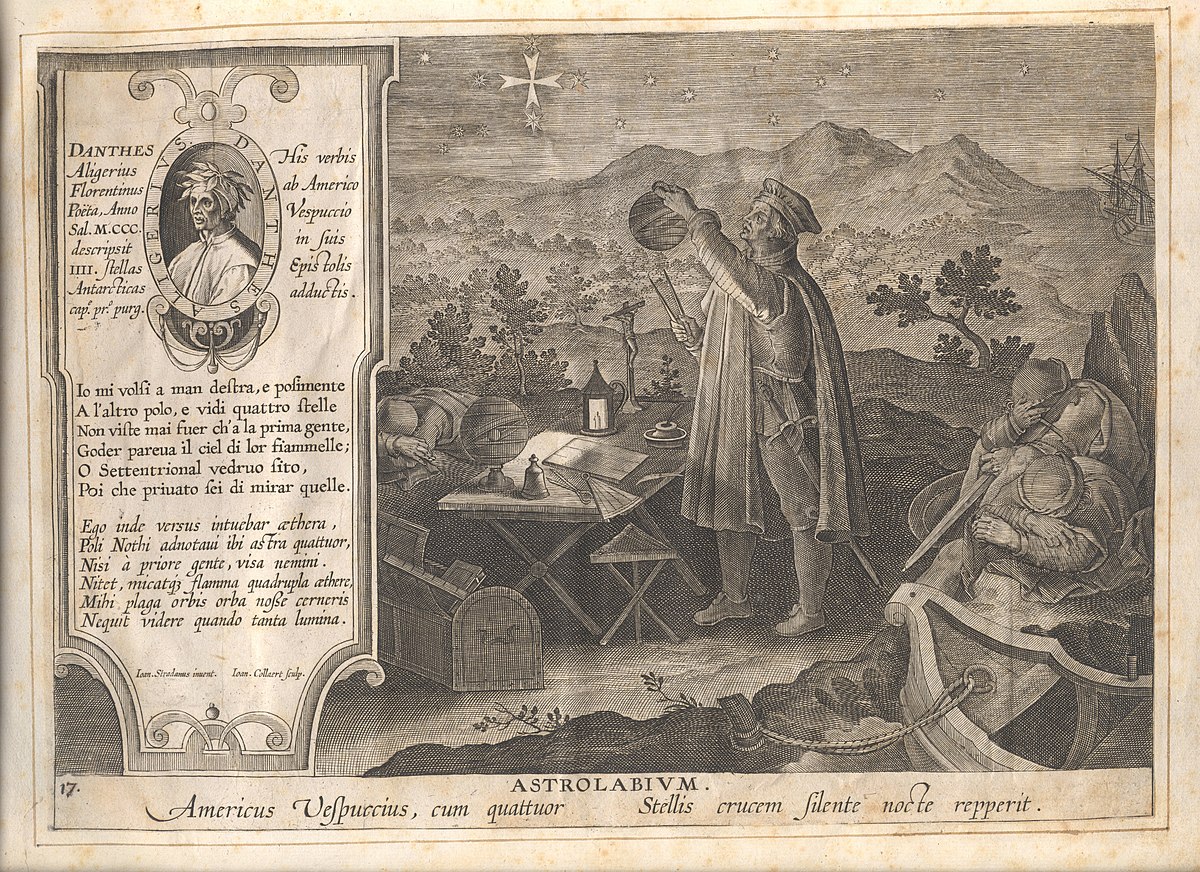

Many - even some Romans - regarded Brutus as a symbol of liberty. But in Dante's Divine Comedy Brutus and Cassius are in the lowest circle of hell, eternally devoured alive in one of Satan's three mouths, along with Judas.

Many - even some Romans - regarded Brutus as a symbol of liberty. But in Dante's Divine Comedy Brutus and Cassius are in the lowest circle of hell, eternally devoured alive in one of Satan's three mouths, along with Judas.

Whether Brutus was treacherous or noble, his plans failed; the republic fell and Rome became an empire.

And that's the 15th March 44 BC, one of those fateful dates etched interminably into the annals of history.

But the question remains: was Brutus a hero or a villain?

And that's the 15th March 44 BC, one of those fateful dates etched interminably into the annals of history.

But the question remains: was Brutus a hero or a villain?

If you enjoyed this then you may like my free, weekly newsletter.

It comes out every Friday and features seven short lessons on art, architecture, history, and literature.

To join 70k+ other readers, consider subscribing here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

It comes out every Friday and features seven short lessons on art, architecture, history, and literature.

To join 70k+ other readers, consider subscribing here:

culturaltutor.com/areopagus

• • •

Missing some Tweet in this thread? You can try to

force a refresh